How to Read “The pot calls the kettle black”

The pot calls the kettle black

[thuh pot kohlz thuh KET-uhl blak]

All words use common pronunciation.

Meaning of “The pot calls the kettle black”

Simply put, this proverb means someone is criticizing another person for a fault they have themselves.

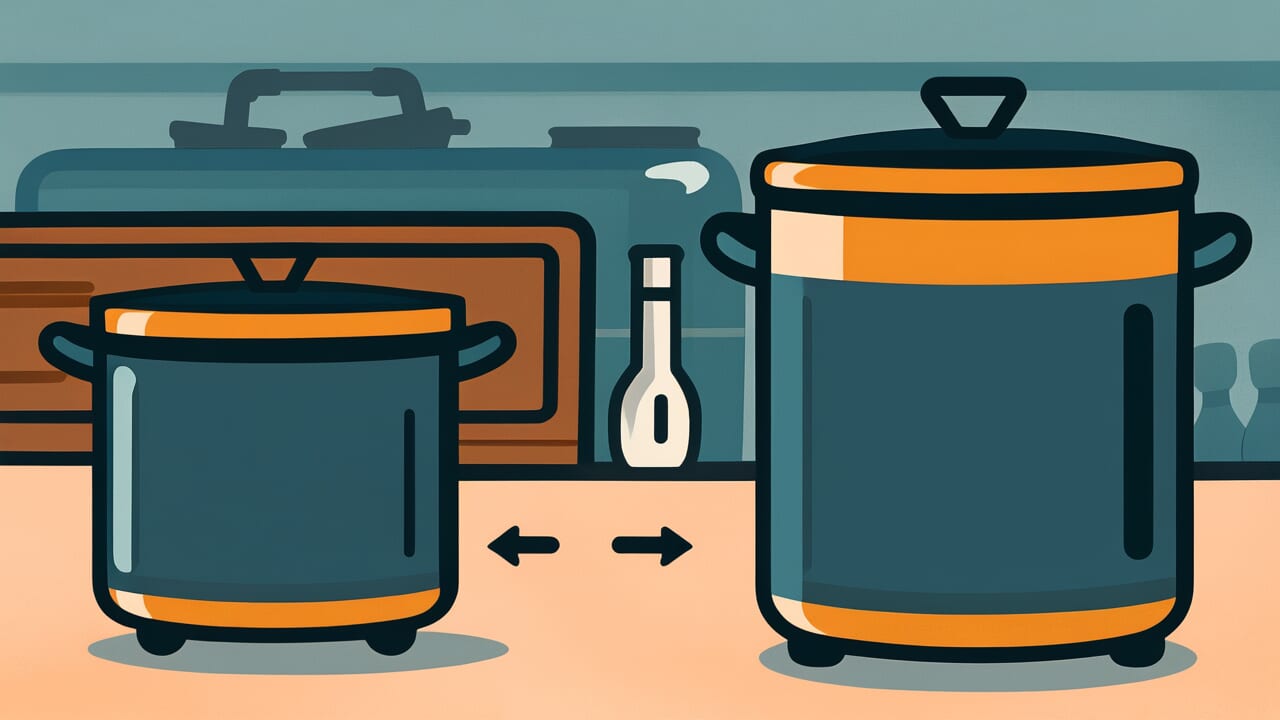

The saying comes from old kitchens where both pots and kettles turned black from soot. If a pot complained about a kettle being black, it would be silly. The pot was just as dirty as the kettle. This creates a picture of someone pointing out problems they also have.

We use this saying when people act like hypocrites. Someone might complain about their friend being late all the time. But if that person is also always late, they’re being a pot calling the kettle black. It happens at work when bosses criticize employees for things the bosses do too.

The proverb reveals something interesting about human nature. People often see faults in others more clearly than in themselves. We notice when someone else makes a mistake but ignore our own similar mistakes. This saying reminds us to look at ourselves before judging others.

Origin and Etymology

The exact origin is unknown, but this proverb appeared in English writing by the 1600s. Early versions sometimes used different cooking items but kept the same basic idea. The saying grew popular because most people understood kitchen life and cooking tools.

During this time period, cooking happened over open fires or in fireplaces. Pots and kettles both sat directly in flames or near burning wood. Soot covered everything used for cooking. The comparison made perfect sense to people who saw blackened cookware every day.

The saying spread through everyday conversation and written works. It traveled wherever English speakers went and became part of common speech. Over time, people kept using it even as cooking methods changed. The meaning stayed clear even when modern kitchens replaced fireplace cooking.

Interesting Facts

This proverb uses a literary device called personification by making pots and kettles “talk” to each other. The image works because both items would look identical when covered in soot from cooking fires. Similar sayings exist in other languages, suggesting this type of hypocrisy observation appears across many cultures.

Usage Examples

- Sister to brother: “You’re calling me messy when your room looks like a tornado hit it – the pot calls the kettle black.”

- Employee to coworker: “He’s criticizing our tardiness when he shows up late every day – the pot calls the kettle black.”

Universal Wisdom

This proverb captures a fundamental flaw in human perception that has puzzled people for centuries. We possess an remarkable ability to spot problems in others while remaining blind to identical issues in ourselves. This isn’t simply carelessness or stupidity. It reveals how our minds actually work.

Our brains evolved to monitor others for signs of weakness, dishonesty, or poor judgment. This helped our ancestors choose reliable partners and avoid dangerous people. But the same mental system that protects us also creates blind spots. We naturally focus outward to scan for threats and opportunities. Turning that same critical eye inward requires extra effort that doesn’t come automatically.

This selective vision serves another purpose too. Maintaining a positive self-image helps us function and take risks. If we saw all our faults as clearly as we see others’ mistakes, we might become paralyzed by self-doubt. The mind protects us by softening our self-criticism while sharpening our judgment of others. This creates the perfect conditions for hypocrisy to flourish without us even noticing it.

When AI Hears This

People don’t just criticize others by accident when they’re guilty themselves. They do it on purpose as a smart social move. When someone points fingers first, others stop looking at them closely. The loudest accusers often have the most to hide. They use moral outrage like a shield to protect themselves.

This pattern works because humans focus on one target at a time. The person doing the accusing becomes the moral authority in that moment. Everyone looks where they point instead of examining the pointer. It’s like a magic trick where attention gets redirected perfectly. The strategy works so well that people use it without thinking.

What fascinates me is how this creates a strange social dance. Everyone knows the game but keeps playing it anyway. The most flawed people often become the harshest judges of others. This isn’t a bug in human thinking – it’s a feature. It lets communities have moral discussions without destroying every member. Sometimes the best way to address problems is indirectly through projection.

Lessons for Today

Living with this wisdom means developing the uncomfortable habit of self-examination before criticism. When we feel the urge to point out someone’s fault, we can pause and ask whether we’ve ever done something similar. This doesn’t mean we can never offer feedback or hold standards. It means approaching criticism with humility rather than superiority.

In relationships, this awareness changes how we handle conflicts. Instead of attacking someone’s character flaws, we can focus on specific behaviors and situations. We might say “this particular action caused problems” rather than “you always do this wrong.” This approach invites cooperation instead of defensiveness. It also opens space for us to acknowledge our own contributions to problems.

The hardest part isn’t recognizing hypocrisy in others but catching it in ourselves. Our minds resist this kind of self-awareness because it threatens our self-image. Yet people who master this skill often become more trusted and respected. They earn credibility by admitting their own struggles before addressing others’ mistakes. This creates an environment where everyone can improve without shame or defensiveness.

Comments