How to Read “You cannot know your parents’ kindness until you eat another’s rice”

Tanin no meshi o kuwaneba oya no on wa shirenu

Meaning of “You cannot know your parents’ kindness until you eat another’s rice”

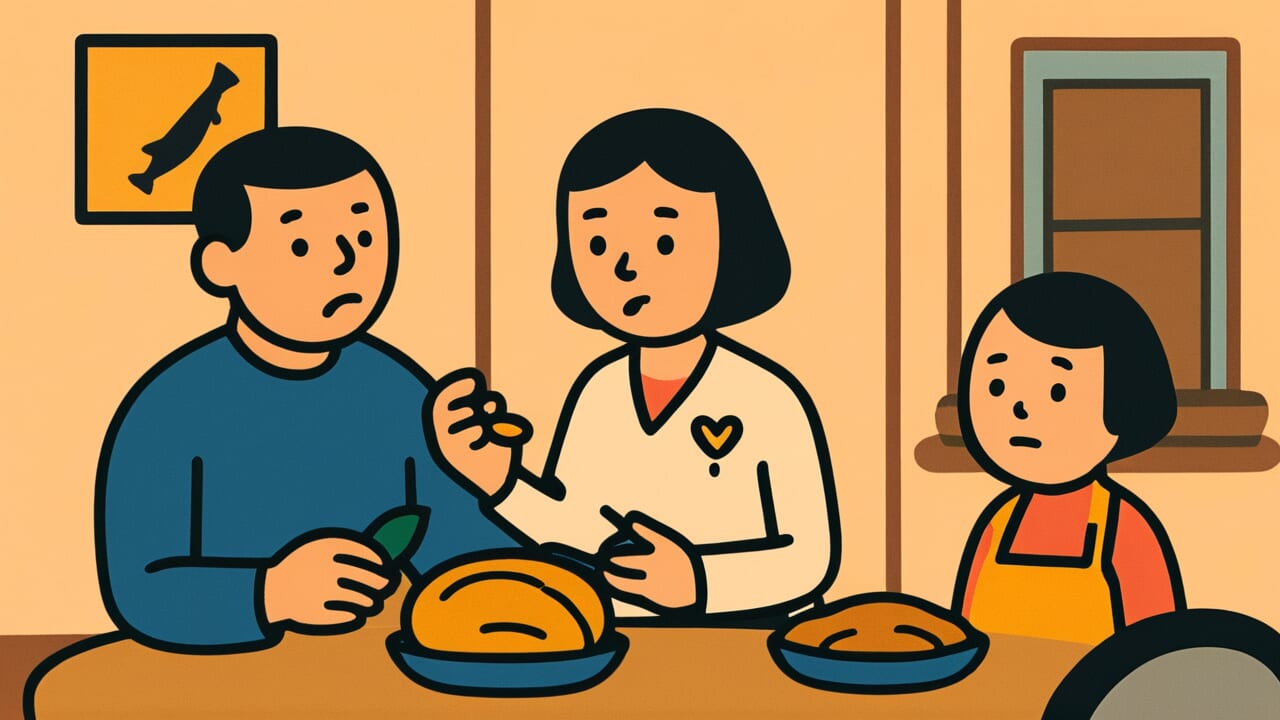

This proverb means you cannot truly understand how deep and valuable your parents’ kindness is until you leave home and experience hardship under someone else’s care.

While living with your parents, their love and care feel natural and ordinary. You don’t notice their value.

But when you actually leave home and live in someone else’s house or go out into society to work, you deeply realize how carefully your parents raised you. You see how much they did for you.

This proverb is used as advice for young people leaving home or entering society. It’s also used to tell people who take their parents’ kindness lightly about the importance of experiencing hardship firsthand.

Origin and Etymology

The exact source of this proverb is unclear, but it likely spread among common people from the Edo period through the Meiji period.

In those days, young people commonly worked as live-in servants or apprentices in other people’s homes. They left their parents and worked in someone else’s house.

Through this experience, they felt their parents’ love and the warmth of home for the first time. This experience probably gave birth to this proverb.

The expression “eating another’s rice” has deep meaning. It doesn’t simply mean eating a meal.

It means being cared for by others and living in someone else’s house. Meals that appeared naturally at your parents’ house must be received with gratitude at someone else’s house.

The taste of meals your parents made, the atmosphere of eating together as a family—these everyday simple joys are things you notice only after losing them.

This proverb also contains the element of “hardship.” In someone else’s house, you must be careful, your freedom is limited, and sometimes you’re scolded harshly.

Through such experiences, you understand how carefully your parents raised you and how tolerant they were with you. This teaching is embedded in the proverb.

Usage Examples

- My son started living alone six months ago. Every time he comes home, he thanks his mother more and more. Seeing this, I realize “You cannot know your parents’ kindness until you eat another’s rice” is truly well said.

- My daughter came back from studying abroad and expressed her gratitude with tears. I experienced firsthand what “You cannot know your parents’ kindness until you eat another’s rice” means.

Universal Wisdom

Humans have a tendency to get used to what’s “normal.” The love and care given every day, no matter how precious, melts into daily life.

Its value becomes invisible. This proverb shows a fundamental human limitation: people can only notice true value through the experience of “losing” something.

Perhaps parents’ love is hard to feel precisely because it’s given freely. Kindness that demands no payment, care that expects nothing in return—these become like air, a natural presence.

They’re not easily recognized as objects of gratitude. But when you’re cared for by others, some tension or hesitation always arises.

Through this contrast, you finally understand how special your parents’ unconditional love was.

This proverb has been passed down for so long because people in every era have had the same experience. When young, you find your parents’ words annoying.

You feel their worry is a burden. You want to become independent quickly. But once you actually leave home, you realize how precious that warmth and security were.

Perhaps humans are creatures who can only learn through experience.

When AI Hears This

The human brain cannot measure the value of things in absolute terms. It judges “good” or “bad” only by comparing with something.

Cognitive science calls this “reference point dependence.” For example, the same temperature water feels warm after putting your hand in cold water, but cold after hot water.

The brain judges using the previous state as a reference point.

Because parents’ care continues every day, the brain sets it as the “standard state”—the reference point itself. Then there’s no comparison target, so its value cannot be recognized.

But when you spend time in someone else’s house, cold treatment or indifference—an “inferior reference point”—suddenly appears.

At this moment, the brain can finally calculate the difference from your parents’ treatment. Through the contrast effect, your parents’ love stands out clearly.

What’s interesting is that your parents’ behavior hasn’t changed at all, yet perception changes dramatically just because the brain’s reference point changed.

Behavioral economist Kahneman’s research shows humans react more strongly to the amount of change from a reference point than to the absolute amount gained.

In other words, we can only measure our parents’ kindness not by “what parents did for us” but by “how different it is compared to others.” This constraint of our cognitive system is the core of this proverb.

Lessons for Today

What this proverb teaches you today is the importance of noticing the value of what you have now.

Not just parents’ love, but many precious things around us become invisible because they’re too ordinary. Friends’ kindness, coworkers’ support, a healthy body, peaceful daily life.

Instead of noticing them only after losing them, you can make the effort to consciously find their value.

If you still live with your parents, try observing their actions starting right now. A casual word, subtle consideration—these contain love that cannot be put into words.

If you’ve already left home, why not contact them occasionally and express your gratitude?

And this proverb applies not just to parent-child relationships but to all human relationships. Don’t take for granted the people who support you now.

This awareness will make your life richer and warmer. Instead of noticing after losing something, you can notice now.

That’s the privilege of those of us living in modern times.

Comments