How to Read “one may as well hang for a sheep as a lamb”

One may as well hang for a sheep as a lamb

[wun may az wel hang for uh sheep az uh lam]

The phrase is straightforward to pronounce using standard English sounds.

Meaning of “one may as well hang for a sheep as a lamb”

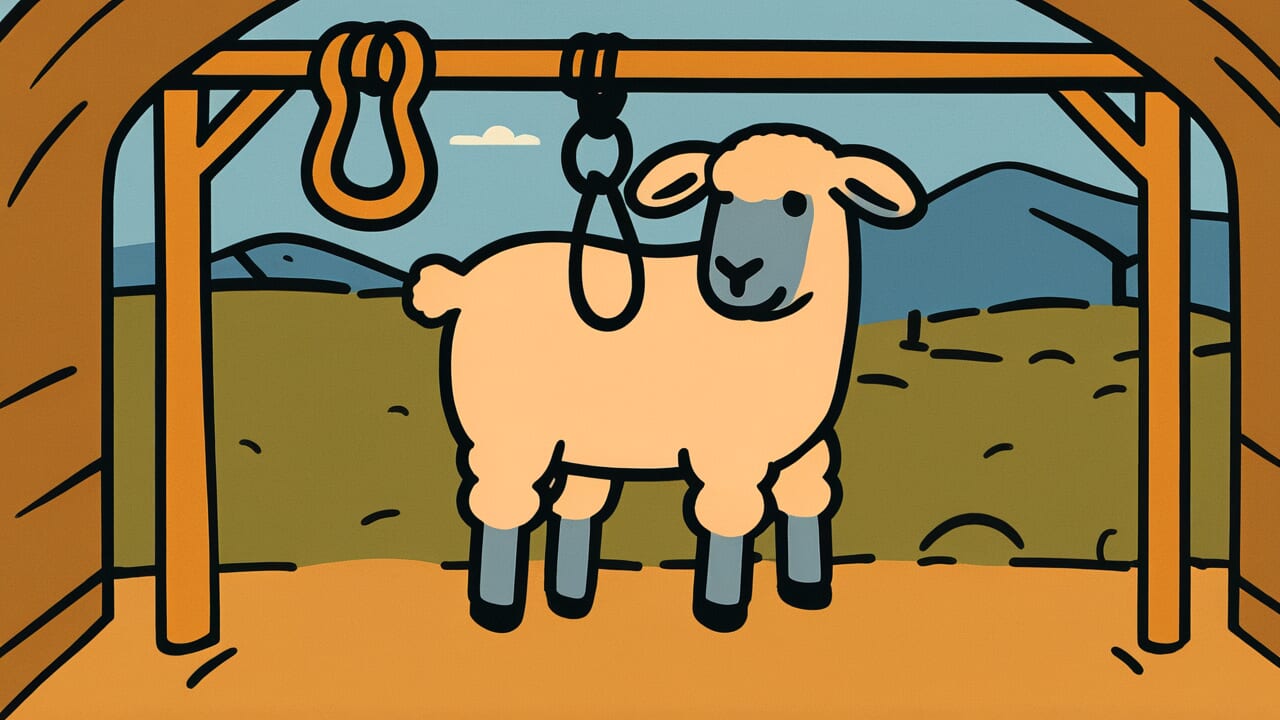

Simply put, this proverb means if you’re going to face the same punishment anyway, you might as well commit the bigger crime.

The saying compares two different thefts that once carried the same penalty. A sheep is much more valuable than a lamb. But if stealing either animal meant facing death, why not take the more valuable one? The proverb suggests that when consequences are equally severe, people might choose the greater offense.

We use this idea today when punishments seem unfair or disproportionate. If getting caught cheating on one test gets you expelled, why not cheat on all of them? If being five minutes late gets you fired, why rush back from a long lunch? The logic feels reasonable when penalties don’t match the severity of actions.

This wisdom reveals something interesting about human nature and justice systems. People naturally weigh risks against rewards. When punishments are too harsh for minor offenses, they can actually encourage worse behavior. The proverb captures this backwards logic that emerges when consequences lose their connection to the size of the wrongdoing.

Origin and Etymology

The exact origin is unknown, but this proverb emerged from England’s harsh legal system of past centuries. During medieval times and later periods, theft of livestock often carried the death penalty. The value of what someone stole didn’t always matter for determining punishment.

In those days, survival was difficult for many people. Stealing food or animals might mean the difference between life and death for a family. Yet the legal system treated many different crimes with the same extreme penalty. This created the strange situation where minor and major thefts faced identical consequences.

The saying spread as people recognized this flaw in harsh justice systems. It became a way to point out when punishments were too severe or poorly matched to crimes. Over time, the proverb expanded beyond theft to describe any situation where penalties seem disproportionate to offenses.

Interesting Facts

The word “hang” in this context refers to execution by hanging, which was a common form of capital punishment in England for many centuries. Sheep theft was considered a serious crime because livestock represented significant wealth and survival resources for rural communities. The proverb uses alliteration with “sheep” and “as” sounds, making it easier to remember and repeat in conversation.

Usage Examples

- Manager to employee: “You’re already late submitting the report – one may as well hang for a sheep as a lamb.”

- Teenager to friend: “Mom’s going to ground me anyway for missing curfew – one may as well hang for a sheep as a lamb.”

Universal Wisdom

This proverb reveals a fundamental tension between justice and human psychology that societies have struggled with throughout history. When punishment systems become too rigid or severe, they can create perverse incentives that encourage exactly the behavior they’re meant to prevent. This reflects a deeper truth about how humans calculate risk and reward in moral decision-making.

The wisdom exposes our natural tendency to seek proportionality in consequences. People have an innate sense of fairness that rebels against punishments that seem too harsh for the crime. When that sense is violated, it can actually undermine the moral authority of the system itself. The proverb captures this psychological reality that lawmakers and leaders often overlook in their desire to appear tough on wrongdoing.

At its core, this saying points to the delicate balance required for effective deterrence. Punishments must be severe enough to discourage bad behavior, but not so extreme that they lose their connection to justice. When consequences become divorced from the severity of actions, they can paradoxically encourage escalation rather than restraint. This reveals why wisdom traditions consistently emphasize the importance of measured, proportionate responses to wrongdoing rather than blanket harsh penalties.

When AI Hears This

People don’t just weigh punishments when making bad choices. They actually switch their entire sense of who they are. Once someone feels labeled as “bad,” their brain stops caring about being good. It’s like flipping a switch that turns off their normal moral rules.

This identity switch happens because humans sort themselves into clear categories. You’re either “good person” or “criminal” – nothing in between. When forced into the “bad” category, people temporarily abandon their good identity completely. Their brain essentially says “I’m already ruined, so nothing else matters now.”

What fascinates me is how this seemingly broken thinking actually protects humans. By going “all in” on being bad temporarily, people avoid the exhausting mental work of constant moral calculations. It’s like declaring emotional bankruptcy to start fresh later. This dramatic either-or thinking, while appearing irrational, gives humans clear psychological breaks from the impossible burden of being perfect.

Lessons for Today

Understanding this wisdom helps us recognize when systems or relationships have created backwards incentives. In personal situations, we might notice when our own reactions to problems are so severe that they encourage worse behavior rather than better choices. Parents who punish minor mistakes as harshly as major ones might find their children stop trying to be honest about small problems.

In work and social relationships, this insight reveals why proportional responses matter so much. When managers treat small errors like major failures, employees may become more likely to hide mistakes or take bigger risks. When friends react to minor disappointments with major drama, it can push people toward more significant betrayals rather than encouraging better behavior.

The deeper lesson involves recognizing that effective boundaries and consequences require careful calibration. Harsh reactions might feel satisfying in the moment, but they often backfire by removing incentives for people to choose lesser wrongs over greater ones. This wisdom suggests that measured responses, while sometimes feeling insufficient, actually create better long-term outcomes by preserving the connection between actions and consequences. The goal isn’t to be soft on problems, but to ensure that our responses encourage movement in the right direction rather than abandoning the effort entirely.

Comments