How to Read “Confess and be hanged”

Confess and be hanged

[kuhn-FESS and bee HANGD]

All words use standard pronunciation.

Meaning of “Confess and be hanged”

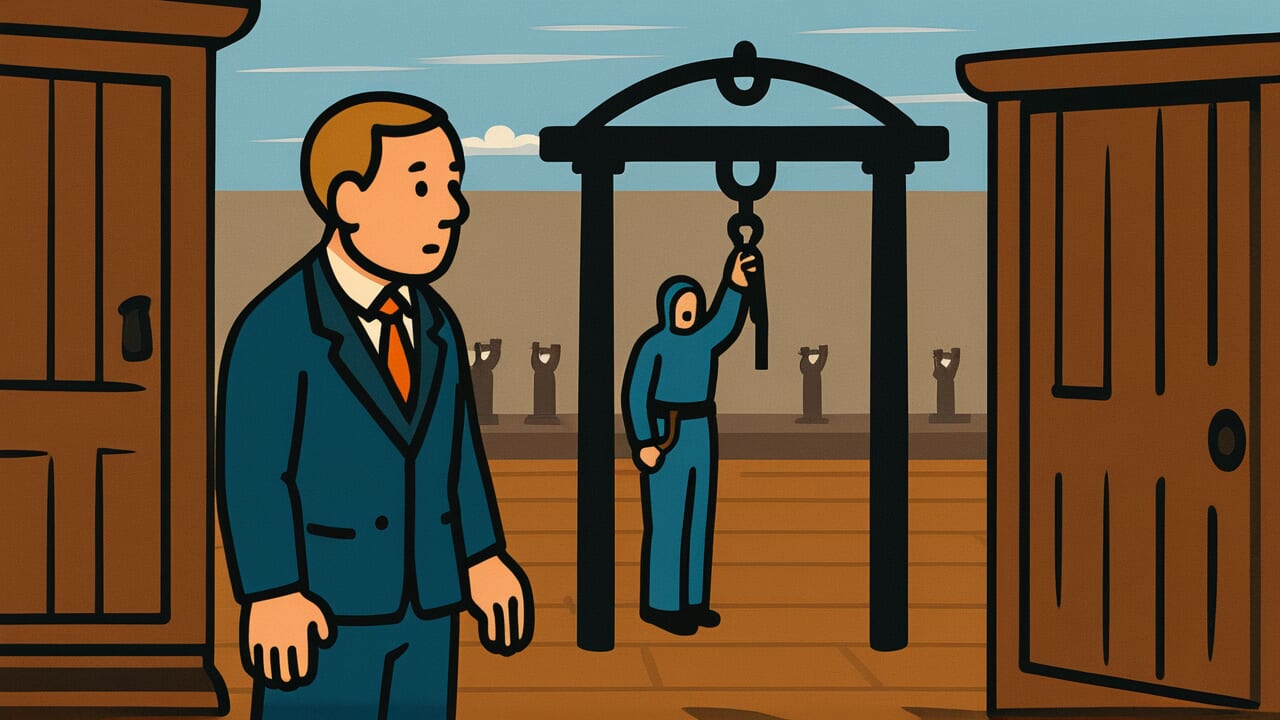

Simply put, this proverb means that telling the truth about your mistakes might not save you from punishment.

The literal words paint a stark picture. Someone confesses to a crime, expecting mercy or forgiveness. Instead, they still face the ultimate punishment. The saying captures a harsh reality about justice and consequences.

This wisdom applies to many modern situations. At work, admitting a costly error might still cost your job. In relationships, confessing a betrayal might not prevent a breakup. At school, telling the truth about cheating might not reduce your punishment. Honesty doesn’t guarantee forgiveness.

What makes this proverb interesting is its brutal honesty about human nature. It warns against naive faith in mercy. People often think confession will make things better. Sometimes it does, but sometimes it just provides evidence against you. The saying reminds us that good intentions don’t always lead to good outcomes.

Origin and Etymology

The exact origin of this proverb is unknown, though it appears in English literature from several centuries ago. Early versions captured the same bitter irony about confession and punishment. The saying likely emerged from observations of legal systems where confession didn’t guarantee leniency.

During medieval and early modern periods, confession played a complex role in justice. Religious traditions emphasized the value of admitting wrongdoing. However, secular courts often punished crimes regardless of remorse. This tension between spiritual mercy and earthly justice created fertile ground for such sayings.

The proverb spread through oral tradition and written works over time. Its dark humor and practical wisdom made it memorable. People shared it as a warning about the risks of honesty. The saying eventually became part of common English expressions about truth-telling and consequences.

Interesting Facts

The word “confess” comes from Latin meaning “to acknowledge fully.” This suggests complete honesty rather than partial admission. The phrase “be hanged” uses an older form of the past participle, which was more common when this saying developed. Modern English would typically say “be hung” for objects, but “be hanged” remains correct for execution by hanging.

Usage Examples

- Detective to suspect: “You’re caught either way – confess and be hanged.”

- Employee to coworker: “Management already knows about the missing funds – confess and be hanged.”

Universal Wisdom

This proverb reveals a fundamental tension in human society between truth and self-preservation. Throughout history, people have faced the dilemma of whether honesty serves their interests. The saying acknowledges that moral behavior and practical outcomes don’t always align.

The wisdom touches on our deep need for justice to be fair and predictable. We want to believe that doing the right thing leads to better results. When confession brings punishment instead of mercy, it challenges our sense of how the world should work. This creates anxiety about moral choices and their consequences.

The proverb also exposes the gap between individual vulnerability and institutional power. When someone confesses, they make themselves defenseless. They hope for understanding but may encounter rigid rules instead. This dynamic appears in families, workplaces, and governments. Those in authority must balance mercy with consistency, while those seeking forgiveness risk disappointment. The saying endures because it captures this eternal human struggle between honesty and safety.

When AI Hears This

Organizations accidentally create backwards reward systems that punish good behavior. When someone admits a mistake, they get fired or blamed. Meanwhile, people who hide problems often get promoted instead. This creates a strange filtering process where honest people disappear. Over time, institutions fill up with people skilled at avoiding blame. The system selects for the wrong traits entirely.

Humans build these broken systems without realizing what they’re doing. They genuinely want honesty and accountability from others. But they also want someone to blame when things go wrong. This creates a hidden trap for truthful people. The same person who demands honesty will punish the first person who confesses. It happens because humans need scapegoats more than they need solutions.

This backwards selection process reveals something fascinating about human thinking. People create systems that work against their own stated goals. They do this unconsciously, generation after generation. The pattern suggests that blame serves a deeper social function than problem-solving. Perhaps punishing confessors helps groups feel like justice happened. Even when it makes future problems more likely to stay hidden.

Lessons for Today

Understanding this wisdom means recognizing that good intentions don’t guarantee good outcomes. Before confessing mistakes, consider both the moral value of honesty and the practical consequences. This doesn’t mean avoiding truth, but approaching it thoughtfully. Sometimes confession brings relief and forgiveness, other times it provides ammunition for punishment.

In relationships, this awareness helps set realistic expectations. When someone admits wrongdoing, they deserve credit for honesty, but that doesn’t erase the original harm. Both parties need to understand that confession is just the beginning of addressing problems, not an automatic solution. Trust rebuilds through actions over time, not just through words.

For communities and organizations, this wisdom suggests the importance of creating safe spaces for honesty. If confession always leads to maximum punishment, people will hide their mistakes instead of learning from them. Balancing accountability with encouragement for truth-telling serves everyone better. The goal isn’t to eliminate consequences, but to make honesty feel worthwhile despite the risks involved.

Comments